She had told me not to run with the lollipop in my mouth, but there I was, galloping my imaginary pony outside the cottage, sucking the sweet green candy and issuing riding commands. Then it slid into the back of my mouth and wedged inside my throat. My first memory of panicked bewilderment: the inability to swallow and blocked breath.

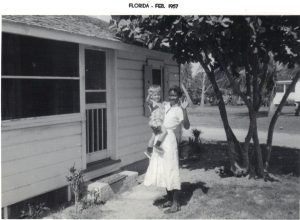

I knew to bang on the porch door off the kitchen. Lois came out, grabbed me by the ankles, and shook me up and down like a sack. The ground came close to my eyes, then fell away and then back until the white stick and glistening candy appeared on the spongy grass.

Bitter tears of fear and pain. A warm embrace.

The boy and I were arguing while standing knee deep in the quiet shore water. He pushed me over backwards and jumped on my chest. His knees pressed on my torso and hands held down my arms. I saw bubbles rising to the surface, felt the salt stinging my eyes and water filling my nose. As I squirmed for freedom my back rubbed against the tentacles of a Portuguese Man of War. A surge of pain and desperation gave me the strength to push him off.

I fled along the path over the dune and across the common yard of the cottages to Lois.

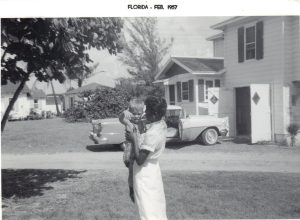

My parents were “snowbirds” from Connecticut.

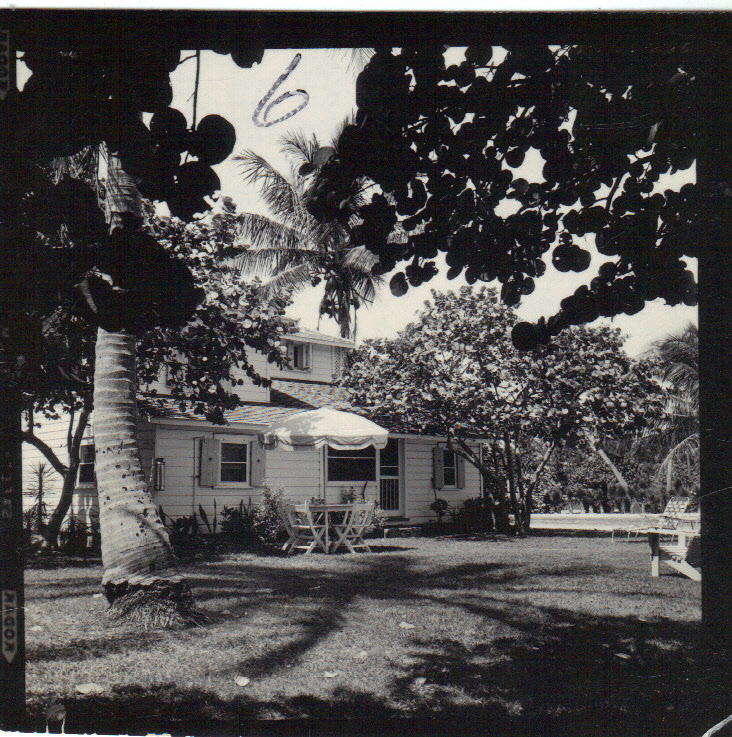

The cottage we lived in from early January to the middle of May was in Pompano Beach, Florida.

The real estate visionary and entrepreneur William L. Kester developed beachfront rental cottages in the 1930s between the coastal road A1A and the dunes, two story homes clustered around a common yard with shuffleboard court and banyan tree. During WW II the cottages were rented to servicemen. My mother was the first long term renter after the war and stipulated improvements be made to “our” cottage.

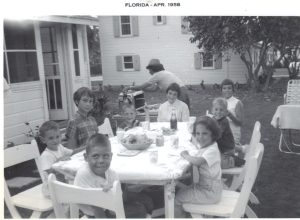

Other Kester residents were Midwesterners and fellow New Englanders, retired couples and Baby Boomer families.

“The rental cottages along the beach provided steady employment

for several black residents of Pompano, whom Kester employed as gardeners,

handymen, and maids.”1

“Shorty” was the friendly man I remember and, according to my mother (in conversations decades later) the unofficial mayor of “Colored Town” who recommended the workers and maids Kester hired. He was a gardener too. After my parents moved north to Boca Raton, he paid us a yearly visit, bringing bushel baskets of fresh vegetables.

My mother also told me that in the evening she would lower the window shades to prevent police from inquiring if they saw a Black person inside. After sunset Black people weren’t allowed within a mile of the beach.

“Upon returning to the Union, Florida reverted to many of its antebellum institutions. Although slavery was abolished, new systems were put in place to maintain White Supremacy. The Poll Tax, White Primary, and segregation in public facilities prevailed.”2

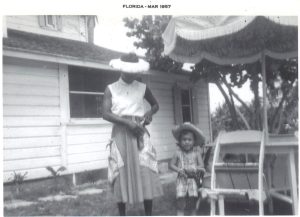

Johnny Rose is the woman in my earliest memories beside my own mother. She was married and sometimes brought her son Sterling to play with me (“Terling” I reportedly pronounced his name).

“They say I was too young

To remember Johnny Rose,

Couldn’t have been more than four,

But the first soulful tones

That I ever heard

Came on wings through the kitchen door.

She fed me and rocked me

That was her job,

Her son was the same age as me,

The one with the world

Reserved in advance

And her own who would fight to be free.

They say I was too young

To know that she drank

She was fired because she stole booze

She went into a hospital

And that’s all they know

But I remember Johnny singing,

Singing her blues”

Tico Vogt 1975

Lois was an unmarried woman in her twenties whom my mother hired as a daytime maid and someone to look after me, the youngest of her three children: Tina 1947, Toni 1948, and Tyke 1953. Her family would have lived on the west side of Pompano’s Wall of Segregation, the “five foot high wall built to separate the then, predominately white neighborhood of Kendall Green to the east from the black neighborhoods of Kendall Lake and Pine Tree Park to the west.”3

She likely had attended school less than 180 days a year because Black children had to work during farming season as Pompano was a busy truck farming hub that shipped winter produce to northern buyers on the Eastern Railroad. Fieldwork had to keep up with “the grueling demands of agriculture work, which started at sunup and ended at sundown for $1 to $1.50 per day. The only leisure time they had was attending church.” 4

How did I perceive her? She was a grown-up person full of lightness and joy, fun loving and caring. I played on the floor near her low-top white canvas sneakers as she stood at the ironing board, pretended to be locked up in chains in a dark dungeon and she’d save me, dressed up as cowboys with her in the yard.

“You named her ‘Lovely’ Lois” my mother told me.

She accepted the offer to move up to Connecticut with us that May. How did she travel? Not in the family car. Train travel for African Americans was highly restrictive even after the 1955 ICC ruling ending segregation. Lois most likely traveled by bus, either to Bridgeport or to Norwalk.

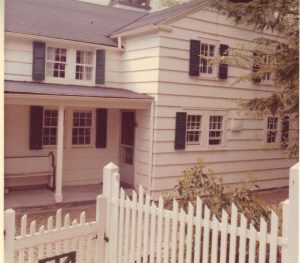

She had a tiny bedroom, a sitting room with a television, bookcase, chest of drawers, and chairs, and a bathroom with a tub. Its windows looked out onto a breezeway that connected the house and garage. A door in the kitchen accessed her apartment.

That July Lois, my parents, and I traveled to my sisters’ summer parent/camper weekend in Casco, Maine, a full day car trip. It would have been a long drive (before the Interstate highways) and typically a difficult one with my dad at the wheel. His attitude was that no one should be in front of him. He camped out in the left lane and invariably passed every vehicle, pulling stunts that caused my mother to shriek and beg him to slow down.

Lois and I, untethered by seat belts, somehow spent the day in the back seat, me with comic books and plastic army men, she with her bible. Outside the car windows passed Bridgeport, New London, and Providence. We stopped in Salem, Massachusetts to visit the Witch House where I put Lois in the stocks and pillories and we ventured into a spooky basement. Then the seacoast of New Hampshire, and late in the day, the lakes and pines of Maine. We arrived in time for dinner at the Edgewater Inn owned and run by Mr. and Mrs. Jacobsen, 1,200 miles north of Pompano Beach.

Lois and I made our way to a second-floor room stuffy with summer heat and the powerful fragrance of Pine-Sol.

Our hosts raised their own vegetables, berries, and chickens. The food was delicious, especially the blueberry pie à la mode.

The next day Mr. Jacobsen took Lois and me fishing in a small aluminum boat. No fish came to my line as we trawled the tea-colored lake, but Lois had the magic touch. She pulled in one silvery perch after another and smiled over my jealous grouchiness.

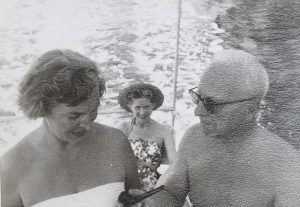

The picture of her holding me at the dock is my favorite. She’s wearing her own clothes with colorful patterns, not a maid’s outfit, and bold jewelry, smiling so beautifully.

In the village there was a small fair we walked to, stopping in the pharmacy to have ice cream or soda pop. There were the typical rides and activities. Did people react to seeing a Black woman?

That fall Tina and Toni were in elementary school and I began kindergarten. My dad drove over to his office in Westport every morning. The house must have been very quiet and a lonely place for Lois.

She would greet me at the bus stop and serve me a snack. If she went down to the basement laundry, I would find activities to be near her, poking around in cobwebbed corners, running my army soldiers through an old-fashioned hand wringer, playing with stuffed animals.

A regrettable memory is of being bathed by my mother and Lois. I asked Lois why her skin was a different color than mine. She explained that she had chocolate milk on her skin. I tried to rub her forearm “clean” and cried when it became obviously futile.

Sampson of the Old Testament was one of my first superheroes. His smiting of armies with the jawbone of an ass and pushing apart temple pillars were about the only Bible stories I warmed up to. The sketch of him in our family’s Daily Roman Missal was frustratingly minimal and disappointing. I shared with Lois my fascination about him, which led her to bring out her Holy Bible, a heavy leather-bound book with gilt edged pages. She opened it to a full glossy color depiction of Sampson fighting a lion. I was transfixed.

One afternoon while she was in another part of the house I gave into an irresistible urge and went into her bedroom, opened her Bible, and engrossed myself in the awe-inspiring image.

Her furious voice broke my spell: “Don’t you touch my Bible! That is MY book!”

There is one photograph of Lois during her time at our home, Sky Ridge. It was taken by the (since) famous married photographers Russell and Betty Kuhner. It was Betty who pioneered the “environmental portrait” that hoped to capture spontaneous joy and interaction among family members. In fact, there was no spontaneity. The proposed settings were ridiculously contrived, as when we siblings had to change into pajamas in the middle of the afternoon and pretend to be awaiting Santa Claus by the fireplace.

On this occasion I had to change out of play clothes and pretend to be at breakfast eating a bowl of Alpha- Bits with Lois watching me. Even as a four-year-old this seemed preposterous and, further, I wasn’t hungry. But come on and eat they said. I resisted their pressure and succumbed to angry tears. Then Lois humored me by arranging the letters into something funny that made me giggle. Snap went the camera.

Her time off began Saturday after lunch. An unfamiliar car would pull into our driveway and Lois, walking across the brick patio and through a white picket gate, disappeared until Sunday evening. My mother explained that she stayed with church friends.

The name Rudolph entered my awareness as a person Lois visited during her time away. I had only heard the name as the famous Reindeer, and it mystified me that it could be a man’s name. It also made me feel jealous and frightened. Would Lois leave to marry him?

Then it was specifically Rudolph who picked her up and took her away.

Lois returned on a Sunday morning instead of the evening as usual. There was a sense of alarm. A cloud darkened her amiable disposition.

Sometime in December my mother told me that we were going to a courtroom with Lois to be her friend while a judge listened to her story. The man Rudolph had tried to do something to Lois, and she had smashed a glass bottle against his head to protect herself.

The courtroom seemed cavernous and cold. The polished benches of dark brown wood were mostly unoccupied. On the witness stand she was dressed in a tan camel hair coat and a tan pillbox hat.

She addressed the judge in serious tones. A bright light was focused on her.

Then Lois was gone.

*

“She said it was a good thing she should leave” my mother said decades later. “She described her affection for you as ‘unnatural.’”

My mother and I had many conversations about the early Pompano Years. What she didn’t tell me was that she had well organized black and white snapshot photos in large envelopes filed as “Kesters” and “Pompano Beach”. The only picture of Lois that I had been aware of was the Apha-Bits one. These envelopes weren’t revealed until after my mother died. What a flood of memories they released. Eventually I combed through all the address books, letters, and correspondences that she had meticulously saved. Lois’ name came up in a few letters my grandmother wrote to my mother, but no last name was ever given.

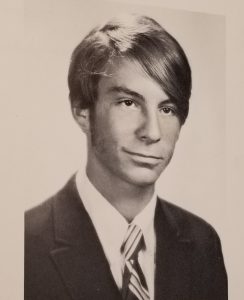

Spring of 1971. My senior year at St. Andrews Episcopal School for Boys. Deep in a late afternoon nap at my parent’ home in Boca Raton.

“Dear, wake up. There’s someone here to see you.”

Someone to see me? I had no plans for any friends to come over, and in our gated community no one just showed up.

In a disgruntled fog I made my way across the wall to wall carpeting toward the muffled voices in the living room.

There was Lois. She was dressed in a denim suit with high black leather boots and large earrings. Her radiant smile.

It was an occasion I couldn’t cope with, standing mute while my mother repeated what Lois had been telling her about her life, that she was a minister of her own church. They continued to talk while I endured complete awkwardness. Lois gave me short glances, perhaps understanding my befuddled, paralyzed state. I watched her head to the front door and turn around for a last smile, missing my chance of a lifetime to say, “I love you, Lois.”

1 Pompano Beach Historic Sites Survey City of Pompano Beach Broward County, Florida 4-13

2 Frank J. Cavaioli PhD. “Pompano Beach: A History” History Press p.17

3 Kevin G. “The (Segregation) Walls That Divide Us” metroatlantic.wordpress.com May 2013

4 Cavaioli p.40

Tico, this was beautiful, truly lovely, just like Lois.

Your comment makes me smile.